April 2024

Amazement

Just a few weeks ago on vacation in Tucson, Arizona, I’m buying a couple of pairs of earrings from Carolyn Reino and chatting with her at her outdoor stall in a small courtyard of shops. The shops are located next to the Franciscan mission San Xavier del Bac, which dates to 1783, on land belonging to the Tohono O’odham Nation. Actor, singer and Navajo silversmith Joe Begay made the earrings, and Carolyn owns the business. I ask Carolyn about the woman’s voice I hear on her radio, and she says she is listening to a tribal council meeting.

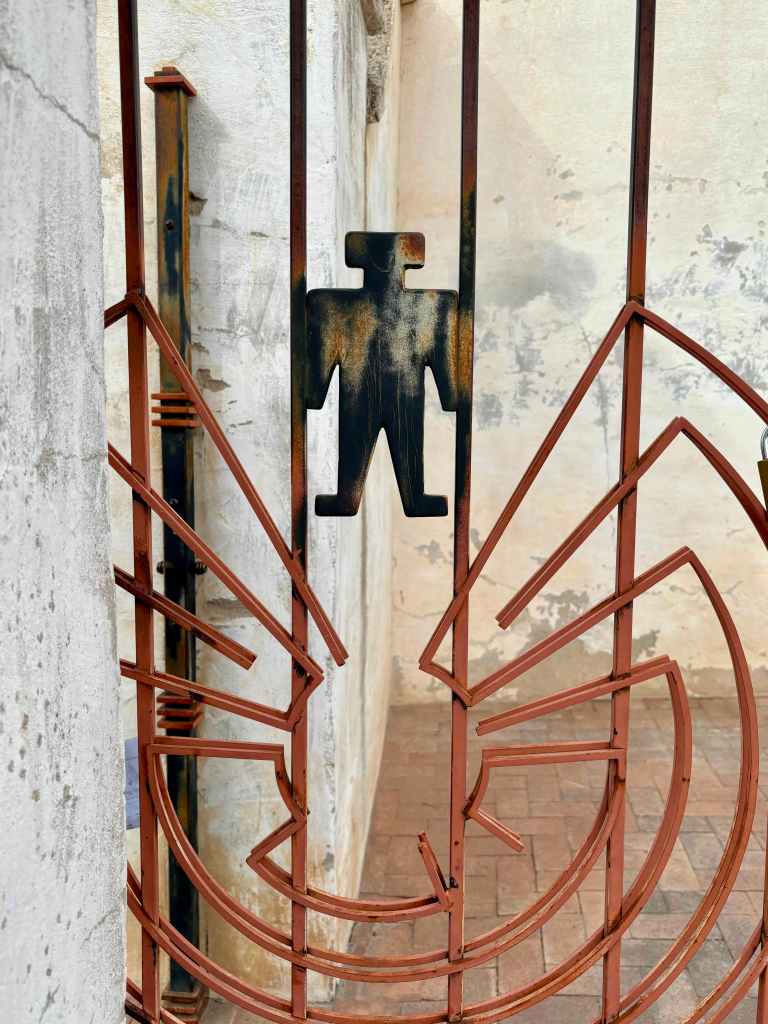

Having just visited the mission, I am curious about the Tohono O’odham symbol that is incorporated into the metalwork of its garden gate, which I then find on stickers and other items in the mission gift shop – and moments later on Begay’s earrings. It’s called I’itoi (pronounced ee-ee-toy), “The Man in the Maze,” and looks like this:

Death approaching

In response to my inquiry, Carolyn hands me a slip of paper that explains:

To the Tohono O’odham, the man at the top of the maze symbolizes the birth of the individual, the family, the tribe and Iitoi (our Creator). As the figure goes through the maze (a person’s life), it may encounter many turns and changes. Progressing deeper and deeper into the pattern one acquires more knowledge, strength, and understanding. As the figure nears the end of the maze it sees death approaching (the dark center of the pattern). Interestingly, it is able to bypass death and retreat to a small corner of the pattern. It is here that it repents, cleanses itself, and reflects back on all the wisdom it has gained in life. Finally pure and in harmony with the world, it accepts death. As a person journeys through their life (the maze), they can feel comfort in the fact that Iitoi is always there to help and comfort them.

She can sense I’m fascinated, which I am for multiple reasons, including because I’itoi depicts the journey to becoming a transformational leader. (By my definition, what makes a leader “transformational” is that, in addition to evolving a team or organization through her external presence, she too is transformed by her leadership as a result of internal growth that only comes from having grappled with darkness.) As I’m thinking this, Carolyn adds that she’s among those who believe I’itoi represents the self-reflective “shadow” journey, which is a more general psychological term for the very same dynamic.

What precisely is this dynamic as it applies to leadership? When we’re holding onto a self-image, a title, a mode of operating, or an identity that we’re in the midst of shedding, we’re “The Leader in the Maze.” Sometimes this can be a painful journey because the overall pattern is not yet visible to us; instead, we’re in the twists of the deepening labyrinth. Without the big picture, the maze can be confusing, exhausting and scary, especially near the dark center. Sensing the unknown and unknowable approaching, we may want to get out of the maze, but as a leader we can’t emerge without changing and being changed – often publicly – in profound ways we cannot predict.

“A small corner of the pattern”

How does this transfiguration work? For me, a key portion of the maze narrative is when the leader who sees figurative death approaching “retreats” to a “small corner” where she surrenders to the unknown. What exactly happens there? The I’itoi information sheet uses the language of repentance, cleansing and purity for what occurs in the corner, whereas for the leadership context I would use the terms humility, self-forgiveness and innocence.

A useful self-coaching question in the small corner is: what must I personally risk for the sake of something larger than myself? When we’re a leader facing an existential threat to our identity – which we recognize by the force of our resistance to change – we can choose to name for ourselves what, precisely, we’re so vigorously defending. This is the humility piece! (Is it my pride or reputation? The importance of being right? The need to justify something I said or did?) When we have a handle on that, a second step – the biggest challenge for many of us – is to forgive ourselves, wholeheartedly and completely. (Will I offer myself love and compassion, and appreciate how I am way more than the part of me that appears to have a “problem”? Will I offer myself grace and let myself be imperfect, wrong – and enough?) Third, we can accept we must let something go, releasing the attached part of our identity along with it, and notice: I may be different, but I’m still here! And when we pause for noticing in this empty, fresh, non-judgmental space, we are in a state of innocence. We’re a beginner at being this new iteration of a leader, and we “know” nothing. From here, we can inquire with pure curiosity: How am I no longer the leader of the self-image that meant so much to me before? What have I out-grown? What next steps does that free me to relax into taking now? Who am I becoming as I walk this path that is walking me?

Final note: seasonal connections

It’s Easter as I draft this post, Passover’s coming up, and Ramadan happens to be occurring right now this year, too. We’re in the season when many of us retreat in spirit to a non-rational place where we give over to life’s greatest mysteries and celebrate what is miraculously liberated in the process. Not coincidentally, these religious observances mirror (in the northern hemisphere) nature’s own bittersweet rites in the sacred violence of birthing, hatching and sprouting. In my view, all of these are intertwined with the universality of I’itoi’s message: take solace in trusting that this incomprehensible pattern – the cosmic cycle of rupture, encounter with death, and an irreversibly altered life on the other side – is not to be understood through the logic in our heads, but through the gate in our hearts.

the Tohono O’odham (Tucson, Arizona) in March 2024.

You must be logged in to post a comment.