July 2023

Can you cleanse your inner vision

until you see nothing but the light?

Can you love people and lead them

without imposing your will?

Can you deal with the most vital matters

by letting events take their course?

— Lao Tzu, Tao te Ching (trans. Stephen Mitchell, Harper, 1988)

Where the inner meets the outer

In last month’s post on The Narrow Way of Leadership, I described a “narrow way” of leading “on the razor’s edge of not-knowing.” By not-knowing, I mean an openness to the continual opportunity for renewal and narrative reframing that springs from the radical uncertainty in every moment. In Zen it’s usually called “beginner’s mind,” but in recent months (thanks to a podcast with Tiokasin Ghosthorse introducing the notion, reinforced by the philosophy of yamabushi monks I encountered on Mt. Haguro in Japan), I have adopted the word “innocence.” It more accurately reflects – in Western, English-language terms – the vulnerability, vastness and potency of this type of awareness in the leadership context.

To be clear, innocence does not equate to lack of knowledge, expertise or political acumen. It is not without guilt, shame, corruption or wrong-doing. Quite the opposite. As a product of grappling increasingly honestly with our brokenness, disillusionment, losses and anguish, the journey of returning home to our innate innocence forges the kind of leadership wisdom that only comes from a dismantling type of unvarnished self-knowledge. Innocence spirals inwardly and outwardly at the same time; the “innocent leader” walks the truth of her experience on the spiraling line between inner presence to herself and presence to her outer dealings.

What are some real-life applications of “innocence” for leaders?

Just in the last couple of weeks, I’ve worked with several executive coaching clients who are in the midst of essential conversations about how they or others will be treated in particular workplace relationships. All are high-heat situations of systemic or structural communication breakdowns that require intervention in order to (1) restore transparency and – ideally – (2) create conditions under which harm can be generatively addressed and professionalism repaired. These conversations involve making declarations, which in the leadership context are statements that interrupt the present to change the future. In the specific examples I’m thinking of, the declarations might be about drawing boundaries on behavior, such as: “This is unacceptable in our organization,” “Stop,” “When X happens, I feel unseen by you,” “What is needed now is…” or “The opportunity from here forward is…”

There is innocence in truth. We can recognize the innocence of a truth by its clarity (and how clearly it comes out of our mouth when we say it). When a leader is standing in the truth of her experience, and voicing it authentically from that place, the declaration is unassailable (no one can persuasively retort, “that’s not the way you feel,” for instance). There is also innocence in the consciousness of a leader who walks the narrow way of the in-and-out spiral; it is less egoic, more curious and listens more deeply. This awareness (which Otto Scharmer, founder of MIT’s Presencing Institute, refer to as “open heart, open mind, open will”) holds an interior space for the leader’s truth, as well as an exterior space that makes room for whatever new truth may come in the wake of a declaration – which may be an even bigger truth.

Of course, speaking our truth – especially an unwelcome truth to certain types of power – can be extremely challenging and is often scary, for good reason. Sometimes it is only worth it when the risk of not saying anything at all is greater than the risk of letting the truth go unspoken. While innocence itself is neither hard nor soft, it can demand a vulnerability from us as leaders that tests our fortitude and our commitment. And voicing truth is a somatic experience: we must feel grounded in our body as well as in our heart and mind if we are to stay meaningfully connected to our animating emotions of anger, sadness or fear and still move forward with courageous action. Audre Lorde, at the Second Sex Conference in 1979, famously observed: “When I dare to be powerful – to use my strength in the service of my vision – then it becomes less and less important whether I am afraid.”

The power of presence

In addition to being physically centered, the precise words we use in our declarations are crucial; “words create worlds” is one of the classic principles of Appreciative Inquiry theory. (In my experience, it’s smart to play on the paradox that simplicity conveys complexity best.) The third and perhaps most magical feature of innocence is its aforementioned open state of consciousness: it is a not-knowing in the ambiguity of the moment, which is actually what allows us to voice our truth in the first place and then “let the chips fall where they may.” That said, innocence is not naivete, and the savvy leader’s presence – her bodily, language, emotional and spiritual focus – affects what becomes possible as a result of her intervention. In practical terms, the tonal quality of attention with which a leader makes a declaration (or does anything else, for that matter) determines the range of what can potentially unfold within, around, through and beyond her. In other words, the eyes through which the leader chooses to see a situation – eyes of compassion, resentment, love, retribution, curiosity, control, generosity, disappointment, gratitude, blame or trust, etc. – determines the future that emerges.

If promoting transparency and creating conditions for the possibility of professional relationship repair are purposes of the leader’s declaration, these would inform her presence and the tonal quality of her attention. A self-coaching question to start with might be: With what eyes do I choose to see this situation?

Additional resources

In a pinch, the “15 Commitments of Conscious Leadership” (scroll down here to find the handout) can be very supportive of a leader’s reflection on the narrow way’s clear voice.

For more about declarations and other leadership “speech acts,” see Chalmers Brothers and Vinay Kumar’s Language and the Pursuit of Leadership Excellence (New Possibilities, 2015). For a how-to book on using Appreciative Inquiry in essential conversations, see Jackie Stavros and Cheri Torres’s Conversations Worth Having (Berrett-Koehler, 2018). For BIPOC and women leaders exploring their authentic leadership voice, I recommend Daphne Jefferson’s Dropping the Mask: Connecting Leadership to Identity (New Degree, 2020). Two other excellent leadership books that cover this territory beautifully – but with very different styles and emphases – are Brene Brown’s Dare to Lead (Random House, 2019), and Jennifer Garvey Berger and Carolyn Coughlin’s Unleash Your Complexity Genius: Growing Your Inner Capacity to Lead (Stanford, 2022).

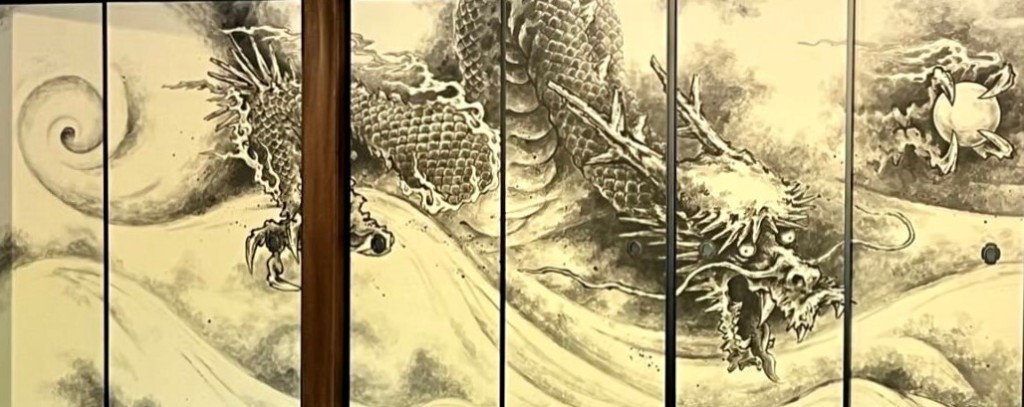

Photo: Susan Palmer, 2023.

Pingback: The Narrow Way of Leadership (Narrow Way, Part I) | Susan Palmer Consulting, LLC

Pingback: Leadership, Innocence and Artificial Intelligence (Narrow Way III) | Susan Palmer Consulting, LLC

Pingback: The Still Point in Leadership Decision-Making | Susan Palmer Consulting, LLC